Charlie Bobo is an oversized twelve-year-old boy, the son of sharecroppers living in 1858 South Carolina in “The Journey of Little Charlie” (Scholastic 2018) by three-time Newbery Medalist Christopher Paul Curtis. Because Curtis is African American and has always written black characters, I was taken aback when Little Charlie bartered with the sheriff.

Eventually, you catch on. Charlie is white. Curtis has him speaking in dialect, which is slightly challenging for the reader. Fortunately, he lightens his touch once the boy’s voice has been established. And we get Curtis’s overall humor throughout.

Charlie describes his huge strong father, Pap, laying ax to tree when the ax head flies off and gashes Pap’s head. “Pap’s backbone went ramrod stiff, standing him straight as a soldier . . . then keeled o’er backward. . . Didn’t nothing bend on him; he jus’ falled straight back like his foots was hinged to the ground.” And the sheriff tells Little Charlie: “[you] look like a man and a half. It’s easy to forget you ain’t nothing but a boy.”

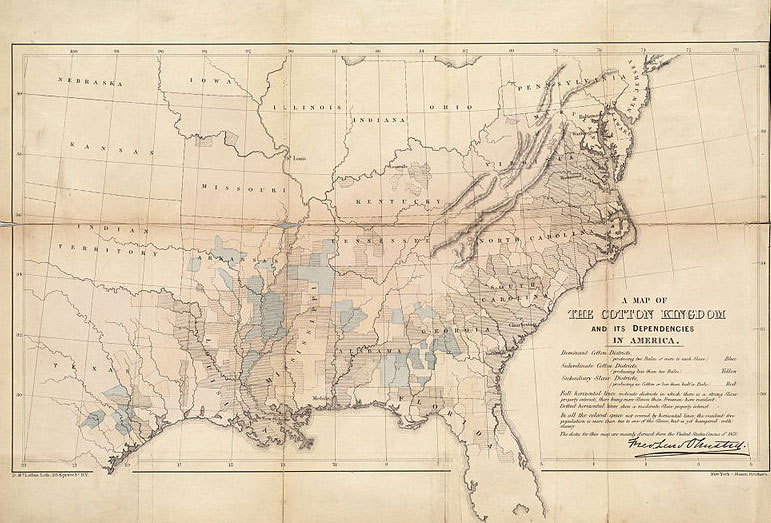

Charlie’s Pap is dead, his sharecropping mother can’t get out of bed, and the overseer, Cap’n Buck, arrives to say they owe him $50. Buck insists Charlie come with him—as pay back—to round up some “darkies” who he says stole $4,000 from the Tanner plantation. Poor Charlie says, “I ain’t never been more’n ten mile from Possum Moan.” In South “Caroliney.”

But off Buck and Charlie ride on horseback up to Michigan. Not only is Buck just about the cruelest human you can imagine, he hasn’t bathed in what seems like years. He stinks bad.

Charlie might seem a trifle dim, but he’s learning fast out in the wild. He remembers Pap saying, “Even dimwits can teach you if you listen careful and pick out the kernels of corn from the horse cr*p they’s dishing out.”

- author: Christopher Paul Curtis

- publisher: Scholastic Press (January 30, 2018)

- binding: Hardcover, 256 pages

- ISBN-13: 978-0545156660

Some pretty horrific things happen, but it’s tempered with humor. Buck finds the two “offending” escape slaves in Michigan, has them jailed, and discovers that they have a grown son in Canada who they could take back to the plantation. Buck and Charlie are advised to clean themselves up because Canada protects its black citizens. Buck has to go through repeated barber latherings before “the cap’n’s skin which went from being brown as any slave you’d see to all the sudden being so white you was tempted to shield your eyes. The whole top of his head looked like a huge chicken had laid a egg there and flewed off.”

You wait for Charlie to see the light of what he’s doing. But when? Canada is a challenge for the slave catchers, but they manage to capture their prey. Now they have three slaves to drive back south. The reader knows, and finally Charlie catches on—the $4000 the slaves were purported to have stolen is the price of their working bodies, their enslaved selves. Simple, impoverished, uneducated, white Charlie gets it: this is very unfair.

And Charlie acts heroically. It’s a simple and devastating story sprinkled liberally with great humor and told so well that it’s a National Award Finalist for 2018.